It doesn't matter if the next president dies or declines

Let's take a walk through history and right-size the panic about Biden's age.

We have become a little bit obsessed of late with our presidential candidates’ health — who does or doesn’t show signs of dementia, who eats more cheeseburgers, who shuffles1 or trips or has a scratchier voice than he used to.

Maybe we’re obsessed because so few of us were around for the last presidential deaths or declines; we simply don’t remember what it is like. That’s a charitable explanation, anyway; it could also be that a big chunk of our population is doped up disinformation and misleading edits, and that major news sources, desperate to appear “objective,” continue to push storylines more concerned with the odds than the stakes.

The future cannot be predicted. Let me say that again: The future cannot be predicted. Aaaand, with two major candidates who are 81 and 77, the odds are higher than usual that in the next few years the United States will experience the incapacitation or death of a president. It might seem crass to say this out loud, but I am certain both men are aware of their mortality, and in any case, it’s a disservice to voters to pretend this isn’t possible.

So let’s hang on lantern on it, shall we? I’ve been down in the history mines, and here is what I’ve found: With one notable exception — the assassination of Abraham Lincoln — a president dying in office has not significantly altered the course of the nation. It’s one of the perks of the whole rule-of-law thing! Similarly, presidents becoming seriously ill or incapacitated have generally been unimportant on a societal scale, with one arguable exception and a couple scary “what-ifs” that are not in play in 2024.

Walk with me: First, we’ll visit the presidents who died in office of natural causes, then at those who were assassinated. We’ll briefly touch on presidents who experienced life-threatening or incapacitating medical events. We’ll evaluate which mattered, which didn’t and why. Finally, we’ll apply these historical lessons to the present day.

FOUR PRESIDENTS HAVE DIED of apparent2 natural causes while in office.

William Henry Harrison died of an illness (probably not contracted by giving a long speech in the rain) a month into his presidency. A pro-slavery son of Virginia, he was replaced by John Tyler, a pro-slavery son of Virginia — not exactly an earth-shaking switch.3

Zachary Taylor was in the conga line of “Who?” presidents — those eight guys you can’t remember between Andrew Jackson and Lincoln. Taylor and his vice president, Millard Fillmore, had views on dealing with slavery that seemed wildly different at the time but were, in hindsight, of the deck chairs/Titanic ilk. After Taylor died of a stomach bug, Fillmore got his deck-chair arrangement with the Compromise of 1850 — the most sweeping attempt to keep the country half slave and half free. It didn’t work, but since Taylor’s plan didn’t include full abolition his idea probably wouldn’t have worked either.

One of the best things Warren G. Harding ever did for himself was die right in the middle of his first term. I’m not being cute here — he was a massively popular president who, soon after his death, was revealed to be a corrupt, philandering fucknut, and it was a net-positive for the stability of the country that he wasn’t still in the White House while all the scandals were being investigated. His replacement, Calvin Coolidge, believed a president shouldn’t do much of anything, which seemed like a good idea up until the fall of 1929, by which point Coolidge had retired. Would Harding have stopped the march toward the Great Depression had he lived? It is impossible to know, but given his chronic indecisiveness, it is unlikely.

When Franklin D. Roosevelt died a few months into his fourth term, it was so, so sad. And probably didn’t make too much of a difference. His huge achievements — the New Deal, winning World War II, SCOTUS nominations — were largely complete, as were his mistakes, like the incarceration of Japanese and Japanese Americans in concentration camps. Once Harry S. Truman took over, he became a consequential president in his own right, but his biggest moves, both foreign and domestic, never ran far afield of his predecessor’s. Even their tussles with the Supreme Court over presidential power were similar. Would Roosevelt have dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki? We can’t know. But we do know the program to build the bombs started on his watch, and he had signed a secret agreement with Churchill picking Japan as a target before his death.

FOUR PRESIDENTS HAVE BEEN assassinated while in office. We’ll look at the latter three first.

James Garfield had all the makings of a lovely president. A Lincoln devotee, he fought a corrupt political machine within his own party and won, before being assassinated by a guy we would now call a stalker.4 His successor, Chester A. Arthur, long allied with the corrupt machine, surprisingly rose to the occasion and continued Garfield’s reforms — perhaps motivated by a secret terminal diagnosis that killed him soon after he left office.

While in the White House, William McKinley embarked on an imperialist jag that, while popular among white male voters at the time, has not aged well at all. After his assassination by an anarchist, his successor, Theodore Roosevelt, continued on the imperialist tear but added the strong domestic agenda that earned him his spot near the top of Best Presidents lists. It’s not that McKinley was so bad or deserved to die, it’s just that his sudden absence turned out okay for the country.

Which brings us to 1963, when Lyndon B. Johnson took office after John F. Kennedy’s assassination. Again, I do not mean to minimize the impact Kennedy’s untimely death had on his family or the psychology of young Baby Boomers. But Johnson’s two big crucibles — African American civil rights and military involvement in Vietnam — were inherited from his predecessor. Johnson is correctly credited with shepherding the Civil Right Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 through Congress. Kennedy was certainly less equipped to pull that off, but had he lived he still would have had Johnson’s legislative expertise in his stable. Would Kennedy have made less of a disaster of the Vietnam War? Once again, we can’t know, but if the Bay of Pigs invasion is any indication, maybe not.

Finally, let’s talk about Abraham Lincoln. Why did Lincoln’s assassination have such a devastating effect on the country, one from which I would argue we are still recovering? It isn’t because Lincoln was a singular man for his times and Andrew Johnson petty and corrupt, though that’s true; far more consequential was that Lincoln was a Republican5 and his vice president a slaveholding Southern Democrat.

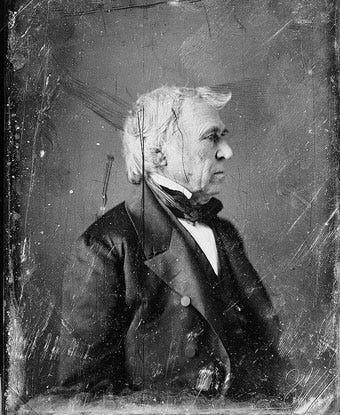

In Lincoln’s first term, his vice president was Hannibal Hamlin, an abolitionist from Maine. The two men weren’t particularly close, but they worked together just fine, and Hamlin loved the Emancipation Proclamation. As the 1864 election approached, the Civil War wasn’t going very well, the radical Republicans revolted and picked their own candidate, and Lincoln expected to lose in November. He picked Johnson as a hail-mary, thinking he would need to court some Democrats in order to stand a chance. But then Sherman marched to the sea, the radical candidate stood down, and Lincoln won in an electoral landslide.

It’s generally unwise to engage in alternate histories, but let’s be foolish for a moment and suppose Lincoln had stuck with Hamlin and still been reelected. Would Lincoln’s life have been spared had Southern-sympathizing John Wilkes Booth thought Lincoln’s replacement would be more of the same? Even if Booth had still killed Lincoln, what would our country be like today if a President Hamlin had actually carried out Field Order No. 15, reallocating Confederate land to newly emancipated and soon-to-be partially franchised Black Americans?

In any case, we got Johnson, a self-centered racist more concerned with extracting servility from his defeated Southern rivals than in compensating and protecting Black Americans. Lovers of justice still weep.

NOW, LET’S TAKE A LOOK at presidents who have experienced incapacitating or life-threatening medical conditions while in office, and the few that might have been significant.

George Washington nearly died of the flu and pneumonia during his first term, which, without a clear succession plan or another “uniter” of his stature, could have caused the country to die with him.

As mentioned above, Arthur received a diagnosis of a fatal kidney disease while president, which turned out to be pretty good for the country.

Grover Cleveland6 had a cancerous tumor on the roof of his mouth during his second term, for which he underwent secret surgery aboard a friend’s yacht and wore a hidden rubber prosthesis for the rest of his life. When a journalist found out a month after the surgery and broke the story, Cabinet officials and the president’s doctor lied about it. Had it been acknowledged to the public, or if the cancer had become deadly, it is likely the economy would have fallen into a deeper depression than it was already spiraling toward, according to historian Matthew Algeo.

Woodrow Wilson suffered strokes throughout his life, but the real doozy came toward the end of his second term, while advocating for the United States to join the League of Nations. It is still unclear how incapacitated he was after this stroke; the White House claimed he was still carrying out his duties, but behind the scenes his wife Edith held a tight grip on access to Wilson and was perhaps a de facto president.7 In any case, historians do not agree on the impact this had on the ultimate failure of the League of Nations bid; some surmise Wilson could have negotiated a deal with Congress had he been in a better health, though he notably refused to negotiate before his stroke and either he or Edith continued to refuse after it.

Other instances of presidential medical events did not significantly impact the flow or course of government — whether it be Dwight D. Eisenhower’s heart attack, stroke or Crohn’s disease; Kennedy’s Addison’s disease; Richard M. Nixon’s alcohol abuse; Ronald Reagan’s gunshot wound or possible undiagnosed Alzheimer’s; George W. Bush’s choking on a pretzel or Trump’s coronavirus. If anything, the regularity of presidential medical issues underlines the country’s stability in the face of them.

ALRIGHT. LET’S APPLY all this history to the current possibility of the next president being incapacitated and/or dying of natural causes while in office.

Do we face the young-nation problem that could have arisen had Washington died of the flu? No.

Do we face the nightmare-economy problem that could have arisen had Cleveland’s mouth cancer become known or deadly? No.

Do we face a creating-a-new-world-order problem that arguably occurred with Wilson’s incapacitation? No.8

Do we live in an information ecosystem where a Cleveland- or Wilson-style cover-up would be possible over an extended period, even if attempted? No. Plus, the 25th Amendment, while untested, lays out clearer contingencies for this.

Do we face the problem of a vice president from a different party as actually occurred with Lincoln? No — unless you are one of the absolute chuckleheads being courted by No Labels.

Given the above, history indicates the next president’s incapacitation or death would fall under the crowded category of A Sad Thing But the Nation Is Fine.9

In 2024, there is one ticket whose election will decrease the chances of a national abortion ban in the next four years. Likewise, there is one ticket whose election will increase the chances of an abortion ban in the next four years. And there are a few third-party tickets who, by soliciting votes in certain states, could increase or decrease those chances — even as those tickets have no hope of winning a single electoral vote.10 None of these chances hinge on which person on the ticket finishes the term.

There is one ticket that poses a threat to free and fair elections; there is one ticket that does not. Some may posit that if Trump were elected and then replaced for any reason by his vice president that the threat to democracy would be resolved. I disagree; even in the absence of blatant insurrection, Republicans’ attacks on voting rights predate and will outlive Trump.

If seeing images of dead children in Gaza makes you physically ill and despair for humanity, there is little chance electing Biden/Harris will help with that. Elect Trump/TBD, and there is no chance. Again, regardless of who finishes the next term, this calculation doesn’t change.

I could go down the list of issues, but you get the picture. Whatever deficiencies Kamala Harris is rumored to have as an executive, and whatever efficiencies Trump’s VP pick will probably have in comparison to Trump, neither is likely to steer the country in a vastly different direction than the old man they would replace.

I do not discount how sad it would be if our next president died in office, especially for his family. Jill Biden would certainly grieve deeply; Melania Trump would definitely be at the funeral. But sad and consequential are not the same thing. Let us not be so afraid of a new-to-us experience that we confuse it for an actual campaign issue. Most Americans in history have been through it, and they were fine.

Arthritis happens to lots of people, regardless of age or mental capacity. Normalize shuffling!

I say “apparent” because there are heterodox theories that Zachary Taylor and Warren G. Harding were murdered. These theories don’t matter for our purposes here.

Yes, I am leaving out a lot of bananas-town history here, please don’t write me, Lovers of This Era. I am one of you! I am just saying had Harrison lived we probably still wouldn’t regard him as an important president.

Netflix? Is working on a series about this? Based on Candice Millard’s terrific book? And I can’t wait?

The two major parties slowly realigned their platforms during the mid-20th century. In general, the Democratic Party kept low-key social-welfare stuff and dropped overt racism (note the “overt”), while the Republican Party kept business-friendly stuff and dropped racial justice. Voters generally stayed with or switched party affiliations based more on whether they thought Black Americans deserved access to government programs and less so on philosophies about the optimal size of government. The story, like people, has nuance, but if you have never understood why the first Black lawmakers were Republicans or why segregationist Strom Thurmond started out a Democrat and became a Republican, those are the broad strokes.

I concede this can change quickly.

A tangent: I would consider a constitutional amendment putting an upper limit on a president’s age, not because of health concerns, but because we would be better served by lawmakers more in tune with the generational concerns of the majority, i.e. affordable housing, student debt, drug-law reform, etc. Yes, it would unfairly exclude some vigorous older individuals, the same way some under-35 individuals who could have made great presidents have been excluded for centuries. I also would put like five other things above this on my Constitutional Amendment Wish List.

For the record, I think having only two feasible candidates sucks. Parliamentary systems generally work better at proportionally representing a broader range of views.